Lahore

1929 - 1939

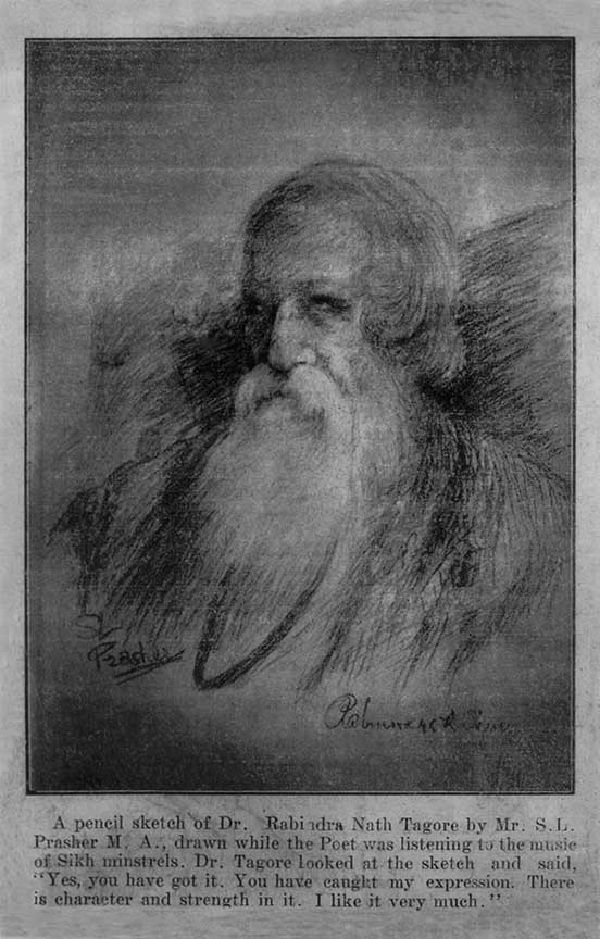

“Yes, you have got it. You have caught my expression. There is character and strength in it. I like it very much.” It was 1931 when Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore had come with his troop of players to Lahore. The poet spoke while they were listening to the music of the Sikh Minstrels and Parasher sketched. Their meeting marks its stamp on the development of Parasher’s art career.

Ambala

1940 - 1959

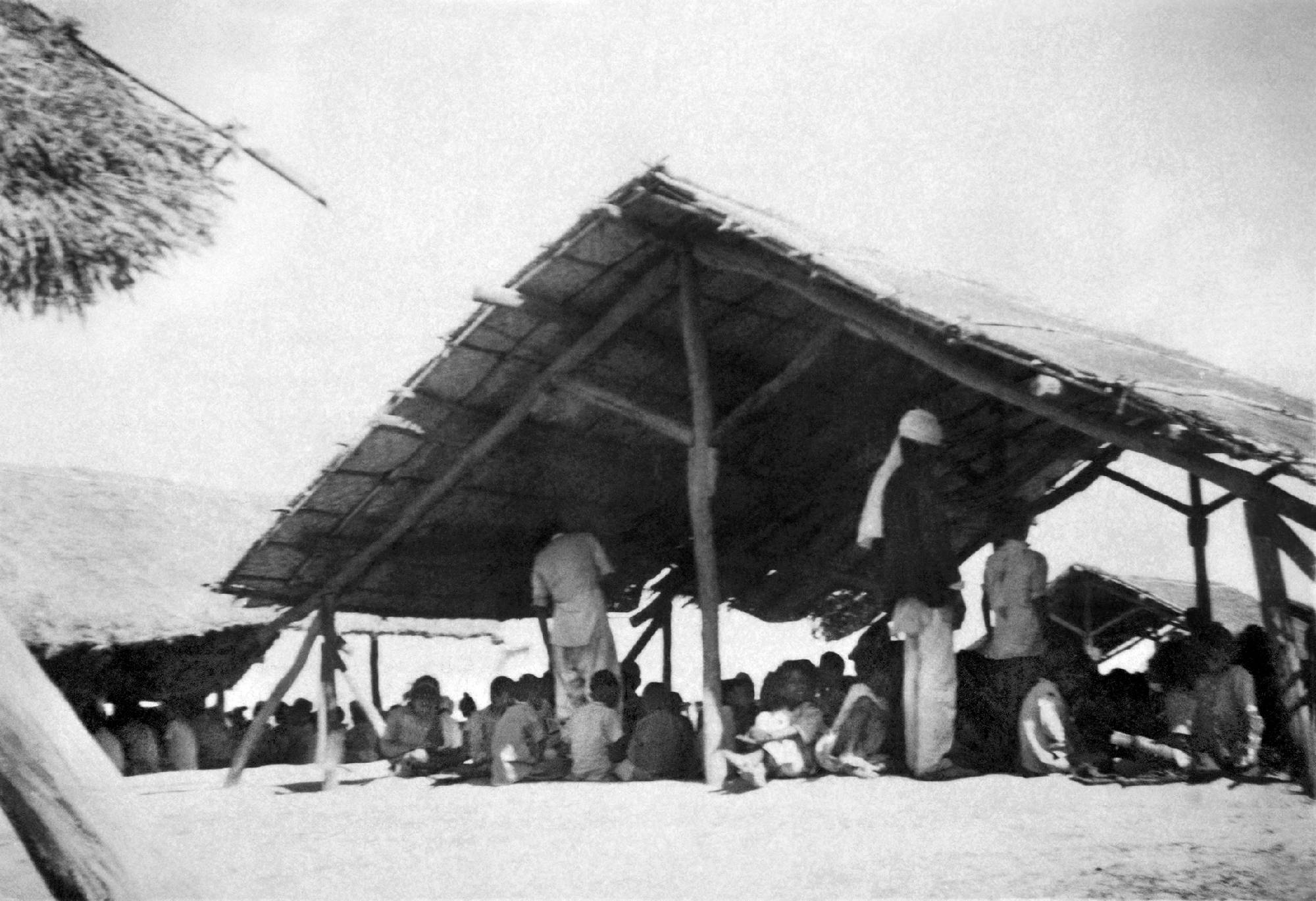

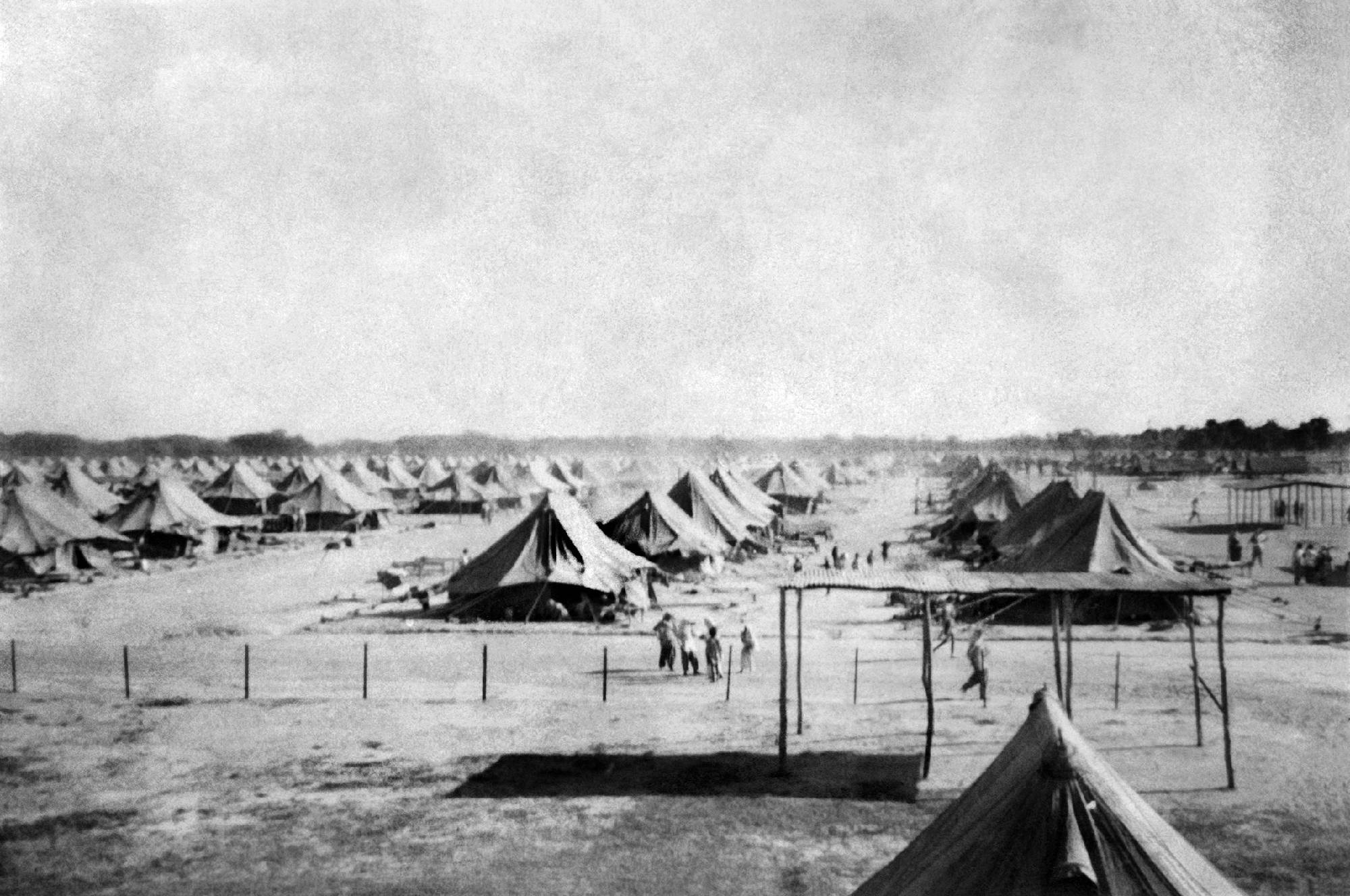

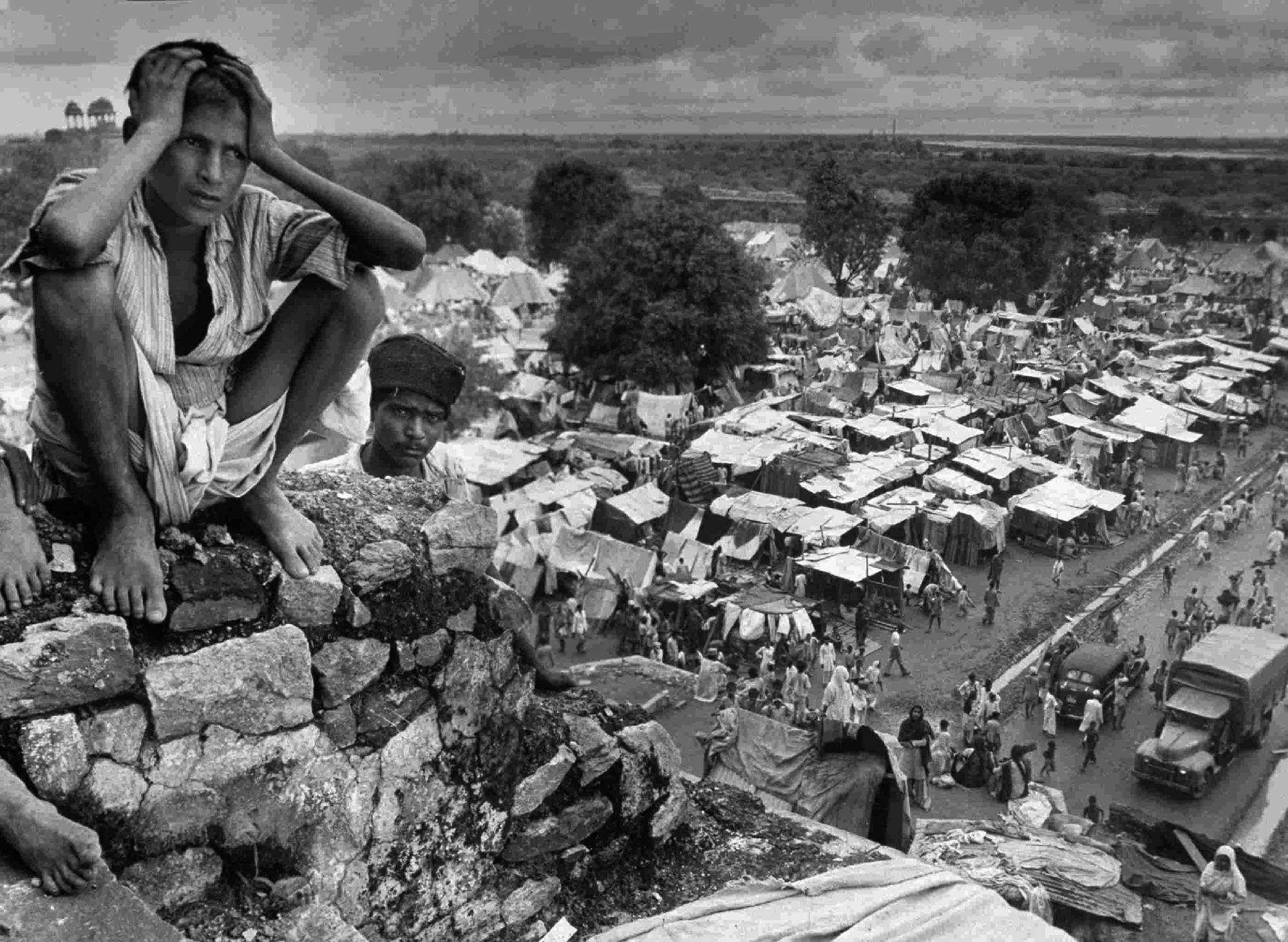

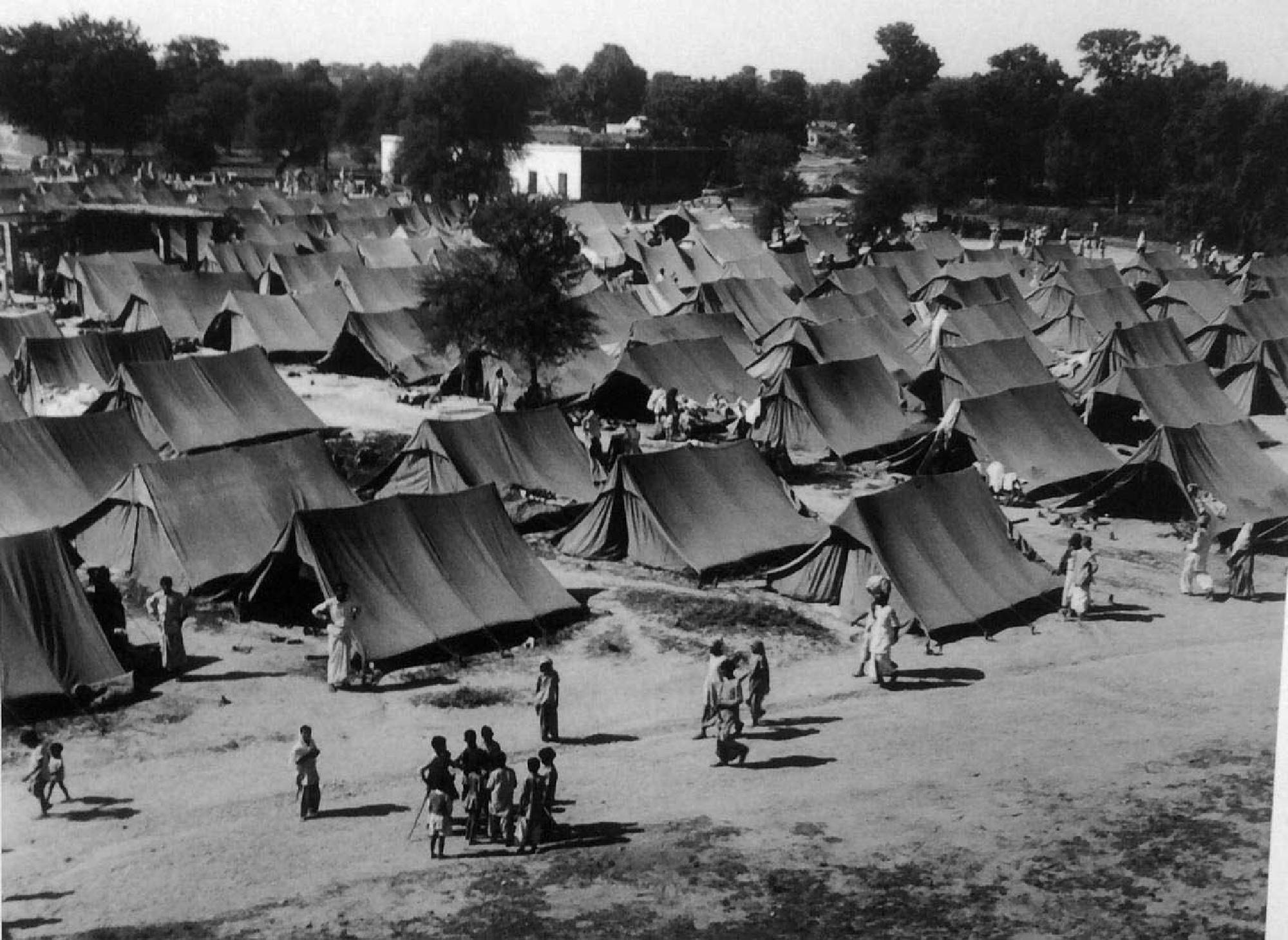

The Amnesia of Grief – Baldev Nagar Camp, Ambala : 1947 to 1949

S.L. Parasher's partition line drawings/sketches

Parasher spent 1945-47 as commandant of the Baldev Nagar Refugee Camp in Ambala. Wrested, like everyone else, from much of what he knew and loved, he spent sleepless evenings walking amongst the refugees and often stopping to sketch the visible evidence of all that was lost. The very fragility of these pieces, they are largely on scraps of available paper, is testament to the nearly impossible journey they have made from that moment to this one. Unlike written records, scant as those are, and unlike recreations such as film, these line drawings are a constant, as real now as they were in the muddy, fly strewn and exhausted moments of their creation.

Shimla

1960 - 1979

The School of Arts was established in this quiet mountain town, the

former British summer capital at the foot of the Himalayas. With

brush, pen, and pencil Parasher captured everyday scenes — hill

people, wild mountains, donkey caravans, school children, women

dancing. Did he know this was the matter of a moment, soon to be gone

forever as the place and its 'new' country brought ever swifter changes?

The sketches and studies are often identified, but by a man with a unique

sense of the important: "2 p.m." "red hat, purple tassels" "Thursday" "no

puppets" The sudden community of the 1950's re-appears before us, all

fragments now, caught like late-season snow under the rhododendrons.

Mumbai

1980 - 1999

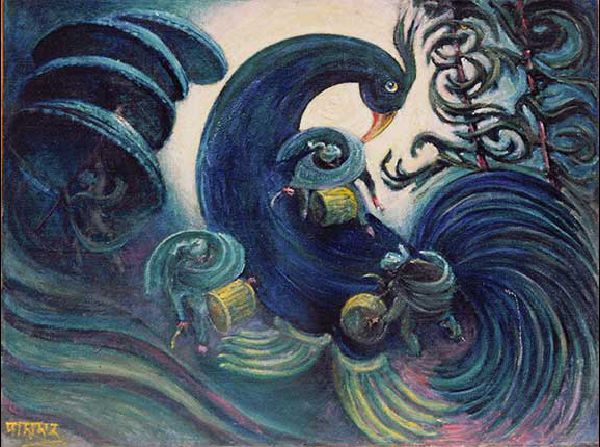

In the early sixties, Parasher was acclaimed as one of India’s most significant sculptors and painters. Despite the modern means employed, his works have the vital quality of rhythmic movement which Parasher claims to be the core part of the ancient Indian tradition; he was aware of the contemporary creative trends but found consanguinity where one might have anticipated conflict. He provides proof, if proof indeed is required - “ I do not believe in masquerading in outward trappings. I hold that art must communicate a deeper experience of one’s being, must express some vision, otherwise it sinks down to the level of external mannerism, just sound and fuss signifying nothing. It is my firm conviction that modernity is first and foremost a matter of consciousness. I do not make images because of my desire to follow any particular style. Nor do I make them to seek new or original means of expression. The aim before me in my work is to discover in my mind the lie of the land, and to strike upon the realm of that land, where it is said forms countless and innumerable are continually fashioned and chiseled. I have come to notice that the images I create carry me, as it were, toward that realm.”

Delhi

2004

In 1959, when Jawarharlal Nehru visited Parasher’s exhibition of sculptures in Delhi, he exclaimed, “Your works are very powerful.” When Le Corbusier selected Parasher’s design for a steel sculpture mural in Chandigarh, he was struck by the intense significance of the forms of his design in relation to the architectural space. “Parasher’s design is ‘most’ interesting.” About this sculpture mural Mulk Raj Anand writing in remarked - “a superb achievement of Parasher.”

Jasleen Dhamija in her article on found, “to my mind, the most exciting mural done so far is done by Parasher at Nirman Bhavan. He has created a mural which is more in keeping with today’s architecture. He uses a pebble surround, within which rise cement concrete shell forms, creating a movement of thrust and counter-thrust. One feels a certain tautness of line and balance of forms. The lines of the pebble background radiate outwards and carry the movement out to the open sky.”

SHARE THIS PAGE!